The best teaching comes from experienced mentors. We publish case studies from veteran functional medicine practitioners to help educate the community on how testing is related to root cause medicine. To order any of the tests from this case study, sign up for Rupa below.

[signup]

Chief Complaint: ADHD, Brain Fog and Fatigue

Mike was a 29-year-old cis male who presented to our clinic with ADHD symptoms, including impulsivity, difficulty concentrating, and procrastination.

He reported that stimulant medication had improved his ADHD symptoms a bit, but he still struggled to focus during the day. He also experienced extreme brain fog and fatigue as his medications wore off (sometimes known as a medication “crash”).

Mike was also experiencing issues with his digestion, insomnia, feelings of low mood, and anxiety. Our shared goal was to help Mike live an energetic, active life filled with calm, peace, joy, and abundant focus.

We aimed to do that by giving him a food-as-medicine and lifestyle-focused plan that would allow him to manage his ADHD symptoms and support his overall well-being. Here’s a bit more background.

Patient History

Mike always had an easy time with school and tested gifted throughout elementary, middle, and high school. He began to struggle academically in college and found that he was also incredibly fatigued, making it challenging to keep up with classes, work, and social life.

Since then, his fatigue and distractibility have persisted and even worsened. Increasingly, he had to pull over to the side of the road while driving to take a nap. He was dependent on approximately 6-8 cups of coffee per day yet frequently fell asleep while at work or school.

He also struggled with interrupted, erratic, and insufficient sleep, as well as severely low moods. Occasionally, he’d wake up in the middle of the night with so much energy that it made him anxious.

When he was able to sit down to study or work, he found that he couldn’t concentrate and would end up reading and re-reading the material multiple times.

Lastly, Mike noticed that he couldn’t put on muscle like he used to; and instead was maintaining fat around his middle section.

Mike wanted help maintaining steady energy throughout the day without caffeine, improved body composition, and higher mood and concentration levels. Here’s how we got him there.

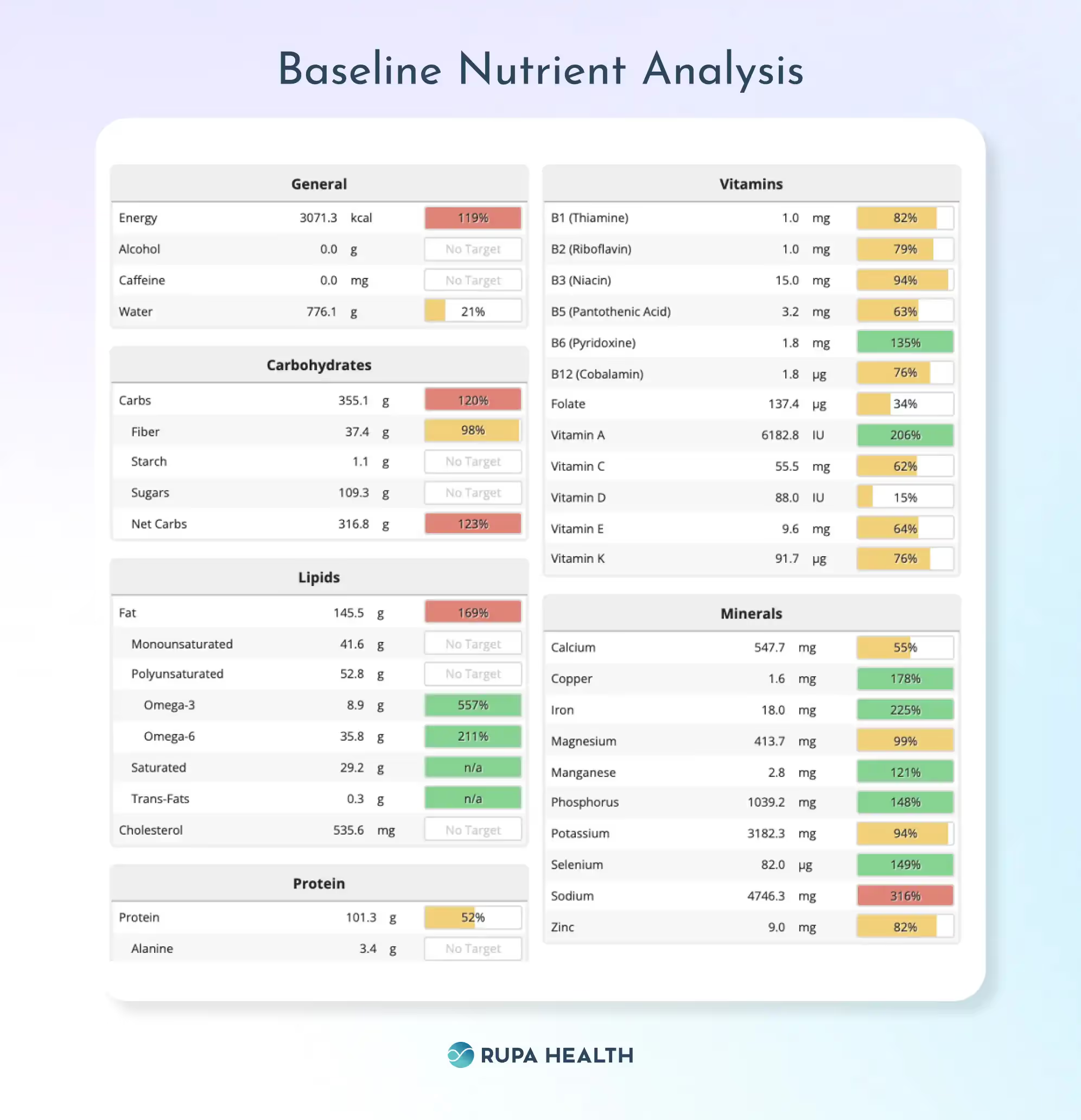

Baseline Nutrient Analysis

Mike’s nutrient analysis revealed that he was low in the vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B12, B9, C, D, E, and K. Mike also under-consumed zinc, which is linked with poor symptom control and a need for higher doses of stimulant medication in people with ADHD.

Additionally, Mike did not consume enough protein (under 53% RDI), which also impacts ADHD by reducing the available tyrosine for conversion to dopamine. His diet was high in processed foods, sodium, and total calories.

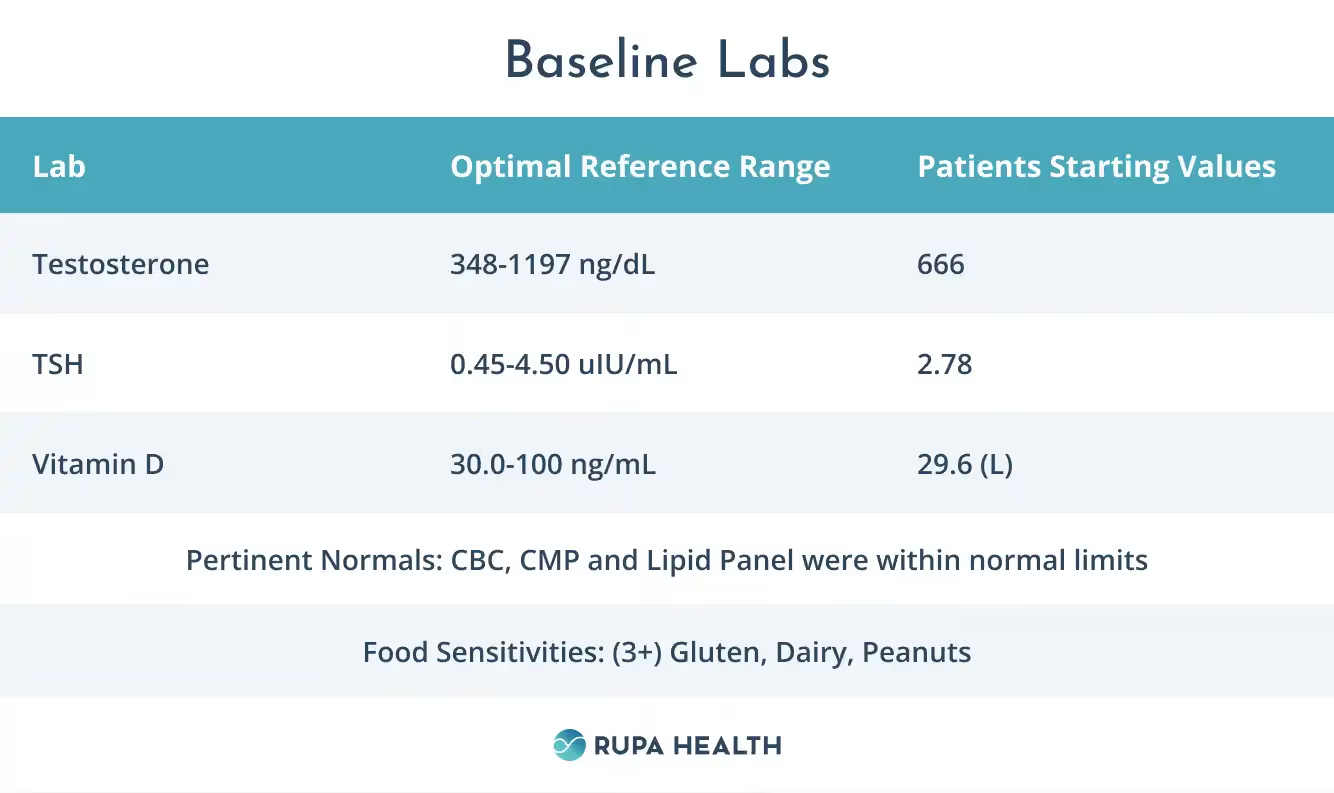

Baseline Labs

Lab Analysis

Mike’s lab work was mostly normal but pointed to a few issues that were reflective of abnormal endocrine function that was contributing to his symptoms of brain fog, ADHD, and fatigue.

- Vitamin D level was low, which is linked to feelings of low mood and ADHD symptoms.

- Food sensitivity results that were ordered by a previous provider indicated a high reactivity to Gluten, Dairy, and Peanuts

- Testosterone and TSH levels were normal, but you will see later in the article that they improve with his protocol, emphasizing the importance of a healthy diet and lifestyle.

Interventions

Nutrition

Mike was guided to try mild time-restricted feeding (TRF) combined with chrononutrition. His eating window was reduced to 12 hours (7 am-7 pm) versus his original 16+ hours eating window.

This was done to support his gut health and encourage optimal autophagy during sleep, which is an essential factor for brain health.

Food sensitivities were swapped out for whole foods products that provided him higher micronutrients, protein, fiber, and omega 3’s.

There are currently many studies that suggest nutritional sensitivities can worsen ADHD symptoms.

Processed, canned, and frozen foods were swapped for meats, vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, and seeds.

His meal plan emphasized easy-to-prepare meals and snacks that he enjoyed to increase his likelihood of sticking with this meal plan. Many people with ADHD struggle to meal plan and cook consistently, so his plan also contained grab-and-go options for the days when he couldn’t prepare meals.

Additionally, his new meal plan aimed to provide him with enough tyrosine and vitamins to support dopamine production each day.

Supplements

- He was guided to take a once-daily multivitamin that contained vitamins A-K, biotin, choline, iodine, zinc, selenium, manganese, chromium, molybdenum, boron, inositol, CoQ10, Alpha lipoic acid, lutein, zeaxanthin, lycopene. Zinc, in particular, is linked to improved outcomes in ADHD.

- Digestive enzymes with meals to support nutrient absorption.

- DIM Detox supplement twice daily between meals to assist with methylation and phase I, phase II liver detoxification.

- Fish oil supplement at 2-4 grams of combined DHA/EPA daily. Red blood cell levels of omega 3 fatty acids are generally lower in people with ADHD, and supplementation can support better outcomes.

Follow Up Nutrient Analysis

Mike’s individualized nutrition plan was designed to be healthy, easy to cook, and fun to eat. It was also designed to address his inadequate intake of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B12, B9, C, D, E, and K.

The nutrient analysis reveals that he has met >100% RDI for these nutrients each day on average for the past six months.

Additionally, he now consumes enough zinc, copper, and iron, which are required for dopamine and adrenaline synthesis and are suggested to support better outcomes in ADHD.

His dietary protein intake increased by nearly 50%, which provides him adequate tyrosine to support adrenaline and dopamine production.

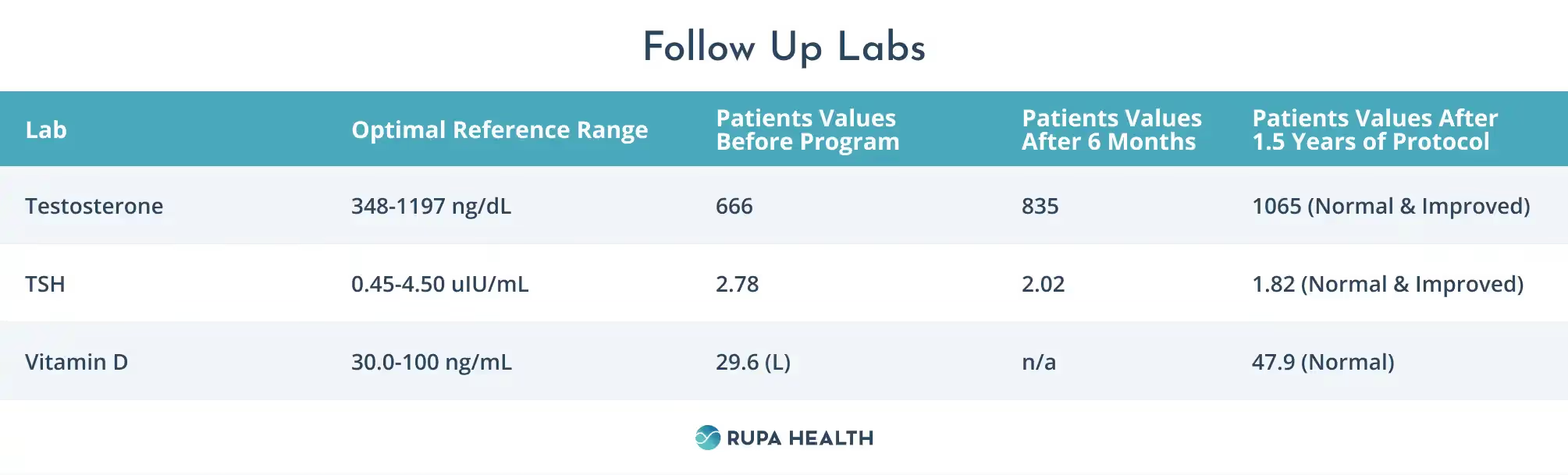

Follow Up Labs

- Vitamin D is now within normal ranges

- TSH, and testosterone levels showed improvement over time with this protocol.

Results From a Functional Medicine ADHD Support Program

Over the course of a year and a half, Mike and I had three more follow-ups. At his third follow-up, he reported that he felt significantly better. His concentration had improved, and his daytime fatigue and brain fog were gone. He had lost fat and water weight and increased his muscle mass. He was no longer bloated and felt that he digested foods much more easily. As a result, his body image had improved, and he looked and felt better.

Mike also reported that he now slept through the night and no longer experienced daytime or nighttime anxiety. His daily caffeine intake had decreased by 50% without associated reductions in alertness, energy level, or focus. He noticed fewer side effects from his medications and was able to experience a noticeable increase in their effectiveness at the same dose. He hadn’t had to pull over while driving in months.

Mike now felt that his ADHD symptoms were more manageable for the first time in years.

Summary

You can support symptoms of ADHD by addressing the whole person. In this case, supporting Mike with a combination of a food-as-medicine plan, supplements, and optimizing sleep helped improve his symptoms and gave him more control over his life, energy, and performance levels.

%201.svg)