In this third article in our anemia series, we shift our focus to macrocytic anemia. Previous articles have established that low hemoglobin and red blood cell (RBC) counts define anemia. It is a common blood disorder affecting up to one-third of the world's population. Macrocytes, larger-than-normal RBCs, present in lower-than-normal numbers characterize macrocytic anemias.

Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that plays many roles in the body, including supporting nervous system function, DNA synthesis, and red blood cell formation. Vitamin B12 deficiency usually takes years to develop due to its large stores in the liver, but macrocytic anemia is a common repercussion when deficiency does occur. Vitamin B12 deficiency is responsible for causing an estimated 2% of all anemias and up to 20% of macrocytosis cases. (6, 12)

[signup]

What is B12 Deficiency Anemia?

Macrocytic anemias may be classified as either megaloblastic or non-megaloblastic, depending on the underlying cause. Megaloblastic anemia is most commonly due to deficiency or poor utilization of vitamin B12 or folate. Non-megaloblastic anemia will not be discussed in detail in this article but may result from liver dysfunction, alcoholism, myelodysplastic syndrome, or hypothyroidism. (1)

Vitamin B12 deficiency most commonly causes megaloblastic anemia. Vitamin B12 deficiency can impair DNA synthesis, producing larger-than-normal cells, called megaloblasts, that are quickly destroyed in the spleen, contributing to anemia (1). To fully understand B12 deficiency anemia, we must go one step further to identify the exact mechanism behind the vitamin deficiency.

Pernicious anemia accounts for 20-50% of vitamin B12 deficiency in adults and is the most common cause of megaloblastic anemia. It occurs when atrophic gastritis or autoimmune processes deplete a protein called intrinsic factor required for vitamin B12 absorption. (2)

Other causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include (1):

- Insufficient dietary intake

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Malabsorption disorders, such as Celiac disease and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI)

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affecting the small intestine

- Decreased stomach acidity

- Surgical resection of the stomach and small intestine

- Alcoholism and B12-depleting medications

Regardless of the cause, vitamin B12 deficiency is most common in the elderly population (12).

B12 Deficiency Anemia Symptoms

Symptoms universal to all types of anemia include (3):

- Cold extremities

- Decreased exercise tolerance

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Irregular heartbeat

- Muscle weakness

- Pale skin

- Shortness of breath

- Atrophic glossitis, a painful, smooth, red tongue, is not specific to but may occur in the presence of B12 deficiency (3).

Complications of B12 Deficiency Anemia

Unresolved anemia is associated with chronic fatigue. In severe cases, anemia is also implicated in the development of heart failure, especially when other cardiovascular comorbidities, like kidney disease, exist.

Untreated, vitamin B12 deficiency may interfere with healthy nerve and brain function, resulting in symptoms like:

- Confusion, slowed thinking, memory loss

- Difficulty with walking and balance

- Peripheral neuropathy: numbness and tingling in the hands and feet

- Uncontrolled muscle movements

Vitamin B12 deficiency is also linked to changes in mood like depression and irritability. This study found a two-fold increased risk of severe depression in community-dwelling older women deficient in vitamin B12.

Pernicious anemia may increase the risk of gastrointestinal cancers.

Functional Medicine Labs to Diagnose B12 Deficiency Anemia

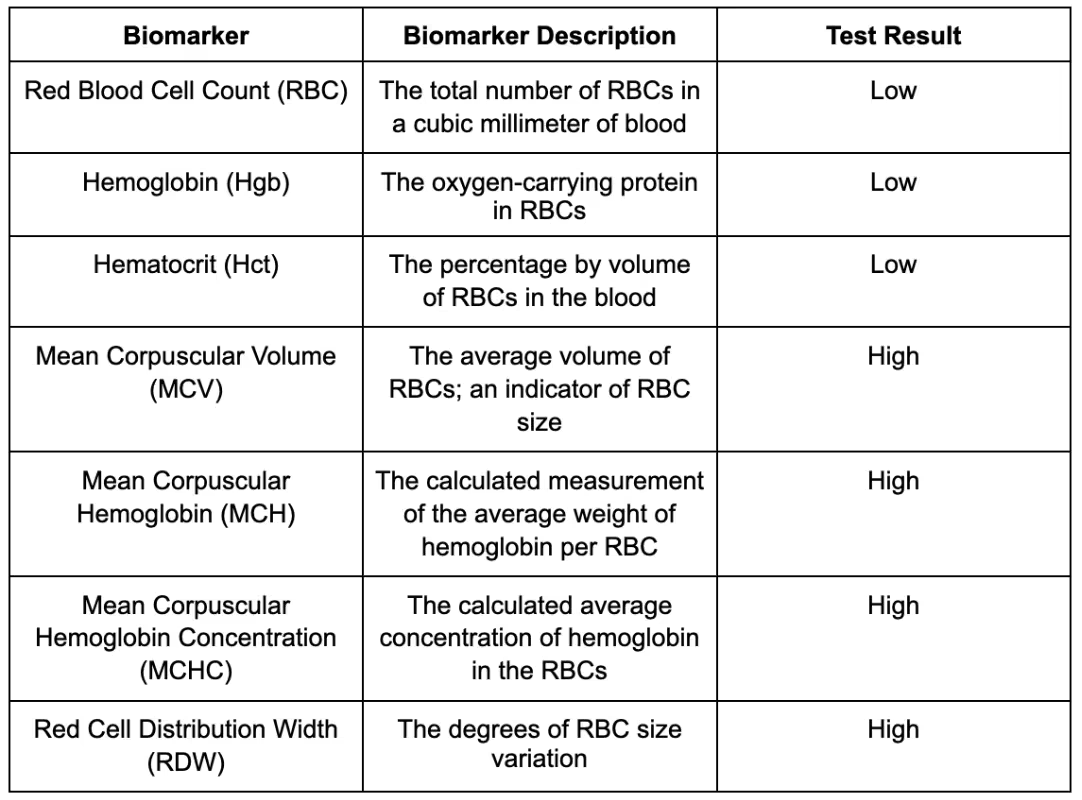

Macrocytic anemia is often found incidentally on routine bloodwork screening. A complete blood count (CBC) is a panel detailing the various types of blood cells. It is used to evaluate overall health and identify a wide range of blood disorders. The table below outlines key findings on this panel that indicate macrocytic anemia.

A peripheral blood smear may be ordered alongside a CBC. This technique examines blood cells under a microscope. Hallmark findings of macrocytic anemia on blood smear include oval macrocytes and hypersegmented neutrophils. (2)

A reticulocyte count may also differentiate between causes of anemia. Reticulocytes are immature RBCs found in abnormal quantities in certain types of anemias. Low reticulocyte counts often accompany pernicious anemia. (2)

Serum vitamin B12 is the preferred initial test for detecting vitamin B12 deficiency. Blood levels less than 200 pg/mL are highly suggestive of deficiency. (4)

For those with a borderline serum vitamin B12 level, measuring methylmalonic acid (MMA) is an appropriate next step. MMA is a more direct measurement of vitamin B12's physiologic activity, and because levels increase in the presence of B12 deficiency, doctors can use it to confirm B12 deficiency. (4)

Homocysteine may also be used to confirm, but is not specific to, vitamin B12 deficiency. Elevated homocysteine can also indicate the presence of folate deficiency, renal failure, and hypothyroidism. (5)

Folate deficiency can coexist with vitamin B12 deficiency and also causes macrocytic anemia. Serum folate should be measured to rule out concurrent folate deficiency anemia, especially when homocysteine is elevated.

Tests for Root Cause of B12 Deficiency Anemia

The presence of intrinsic factor and antiparietal cell antibodies in conjunction with megaloblastic B12 deficiency anemia are highly suggestive of pernicious anemia (5). Pernicious anemia occurs 20 times more frequently in patients with hypothyroidism. Positive intrinsic factor and/or antiparietal cell antibodies should be followed with a comprehensive thyroid panel to assess thyroid function.

Various tests are available to aid in the diagnosis of underlying malabsorptive conditions:

- SIBO breath test

- Fecal elastase is used to diagnose EPI

- H. pylori stool test

- Small intestinal biopsy is the gold standard for Celiac disease diagnosis, but this blood test can measure genetic and immune markers associated with Celiac disease, along with common co-occurring vitamin deficiencies

- Endoscopy/Colonoscopy with biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis of Crohn's disease, but fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin, and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) can help to rule in the diagnosis

Screening patients for excess alcohol consumption can be done in office by administering the AUDIT or CAGE questionnaires. Certain findings on a liver panel, including an AST:ALT ratio greater than two and an elevated GGT, are also highly suggestive of chronic alcohol consumption. (10)

Functional Medicine Treatment of B12 Anemia

Addressing vitamin B12 deficiency is important to support overall health and well-being. This can be approached through diet and supplementation.

Nutrition

Humans must get vitamin B12 either from diet or dietary supplements. Animal products, including meat, fish, poultry, dairy, and eggs, contain the highest amounts of vitamin B12. B12-fortified cereals and some nutritional yeast products also contain bioavailable B12. People following a vegetarian or vegan diet may have an increased risk for vitamin B12 deficiency; supplementing with vitamin B12 could be beneficial for this population. (6)

Supplements

Traditional treatment for B12 deficiency often involves intramuscular (IM) vitamin B12 injections. Treatment schedules for IM injections vary depending on the cause and severity of B12 deficiency but usually consist of loading doses followed by less frequent maintenance injections. A common regimen may consist of daily IM injections for two weeks, followed by a maintenance injection every one to three months. Replacement therapy should continue until B12 levels are normalized and the underlying cause of deficiency is addressed. People with pernicious anemia may require lifelong B12 replacement. Follow-up by remeasuring vitamin B12 markers is recommended to assess response to treatment two to three months after initiating therapy.

Perhaps surprisingly, more data suggests that oral vitamin B12 replacement may be just as effective as IM injections. Evidence supports an alternative route of B12 absorption via mass action effect; it is estimated that 1-3% of high oral doses are absorbed in this manner, even without intrinsic factor or an intact small intestine. Overall evidence quality for supporting oral supplementation in the context of B12 deficiency is low; however, this is an option for those looking for a more convenient and cost-effective alternative to IM injections. (7-9)

Address the Gut

Implementing a gut healing protocol may help manage underlying maldigestion and malabsorption so that long-term dependence on vitamin B12 supplementation is not required to maintain optimal B12 status. Functional medicine practitioners often implement an approach referred to as the "5 Rs," which encompasses the principles of: remove, replace, reinoculate, repair, and rebalance (11). This generalized protocol serves as a gut healing template to optimize digestive function but should be customized to an individual's medical history, lab findings, and preferences.

SIBO and H. pylori, well documented as contributing to the development of B12 deficiency, should be addressed when diagnosed in the context of B12 deficiency anemia. This can be done with a variety of natural and prescription antibiotics.

Supplementing hydrochloric acid and pancreatic enzymes with meals in those with decreased stomach acidity and EPI, respectively, may support the digestion of B12-rich foods and the absorption of vitamin B12.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications like abstaining from alcohol consumption, forming healthy sleep habits, and managing stress can support gut health and B12 absorption (11).

For those taking B12-depleting medications like proton pump inhibitors and metformin, abrupt discontinuation of medications can be dangerous and should never be done without consulting your doctor. Integrative treatment approaches to heartburn and diabetes may allow you to decrease, and even discontinue, your use of prescription medications.

Summary

Vitamin B12 plays many important roles in the body, and having low levels can have serious health implications - B12 deficiency anemia is one of these. Ensuring your diet is rich in vitamin B12-containing foods, addressing other underlying causes of B12 deficiency, and supplementing with vitamin B12 as needed to ensure sufficient B12 status may help manage and support overall health in the context of megaloblastic B12 deficiency anemia.

%201.svg)