Ehrlichia IgG

Ehrlichia is a group of tick-borne, intracellular, gram-negative bacteria that cause ehrlichiosis, an infection primarily affecting white blood cells and manifesting as a flu-like illness with potential for severe complications in vulnerable populations.

Distinct Ehrlichia species, such as E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, and E. muris eauclairensis, differ in clinical severity and epidemiology, underscoring the importance of prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent complications like respiratory failure, neurological deficits, and multi-organ dysfunction.

What is Ehrlichia?

Ehrlichiosis is a bacterial infection caused by Ehrlichia species (E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, E. muris eauclairensis), transmitted through tick bites.

Ehrlichia species are intracellular, gram-negative bacteria that resemble Rickettsia; it primarily infects white blood cells, leading to flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle aches, chills, and fatigue. In severe cases, respiratory failure, neurological symptoms (confusion, meningitis, coma), and multi-organ dysfunction may occur, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

E. chaffeensis can cause fatal illness, whereas no deaths have been reported from E. ewingii or E. muris eauclairensis infections; case-fatality rates are highest in children under 10 years and adults over 70 years.

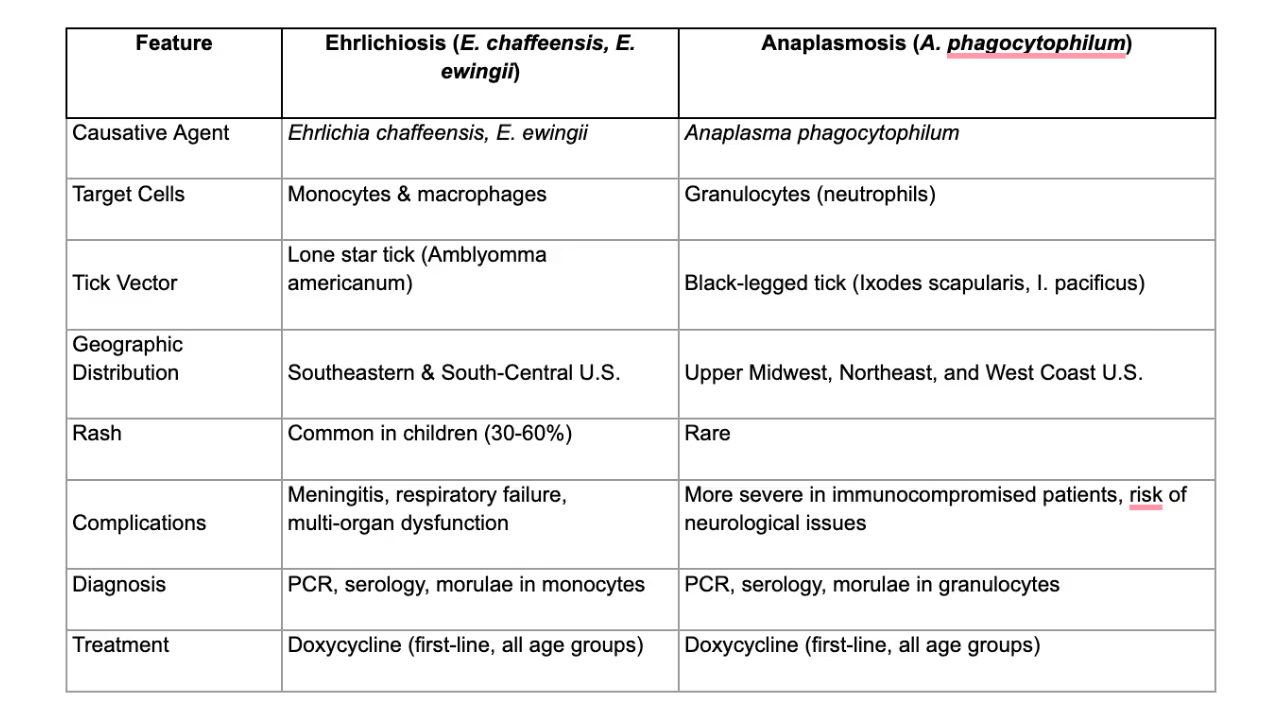

Distinguishing Ehrlichiosis from Anaplasmosis

Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are both tick-borne illnesses with overlapping symptoms, but they differ in the following ways:

Diagnosis & Laboratory Findings

Ehrlichiosis should be suspected in patients with recent tick exposure who develop acute febrile illness with leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Laboratory findings may include:

- CBC: Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, mild anemia

- Liver Function Tests: Elevated AST/ALT (seen in ~85% of cases)

- Electrolytes: Hyponatremia (~40% of cases)

- Blood Smear: Morulae (intracellular inclusions) in monocytes (E. chaffeensis) or granulocytes (E. ewingii), though this is seen in <10% of cases

- PCR: Most sensitive in early infection; loses sensitivity after antibiotic treatment

- Serology (IFA IgG testing): A fourfold rise in IgG titers between acute and convalescent samples (2-4 weeks apart) confirms infection

- CSF Findings (in cases with neurological involvement): Mild lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein

Note: IgM antibodies are unreliable due to false positives and should not be used alone for diagnosis.

Treatment & Management

Doxycycline is the first-line treatment and should be started immediately upon suspicion to prevent complications. Do not delay treatment while awaiting lab results.

Typical treatment regimens may include:

- Adults: 100 mg twice daily (oral or IV)

- Children (<100 lbs/45.4 kg): 2.2 mg/kg twice daily (oral or IV)

- Duration: 5-7 days, continuing at least 3 days after fever resolution

No alternative antibiotics are recommended for ehrlichiosis in children—studies show no risk of dental staining from short-course doxycycline.

Complications

Severe cases may progress to:

- Respiratory failure & ARDS

- Meningitis, encephalopathy, seizures, or coma

- Septic shock-like presentation with cardiovascular instability

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)

- Multi-organ failure (liver, kidney)

What is Ehrlichia IgG?

Ehrlichia IgG is a type of antibody produced by the immune system against the Ehrlichia bacterium.

These antibodies remain detectable long after the infection resolves, serving as markers of past or present infection.

While IgG antibodies to Ehrlichia can be present in both active and past infections, their presence alone does not confirm active disease.

Who Should Get Tested for Ehrlichia IgG Antibodies?

Ehrlichia IgG antibody testing is primarily used to assess past exposure to Ehrlichia bacteria. It may be useful for:

Individuals With a History of Tick Bites and Past Symptoms of Ehrlichiosis

Those who previously experienced fever, headache, muscle aches, or fatigue following tick exposure may benefit from testing, even if their symptoms have resolved.

Differential Diagnosis of Other Tick-Borne Illnesses

Ehrlichia IgG testing helps distinguish past Ehrlichia infections from conditions like Lyme disease or Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Epidemiological Studies

IgG testing is often used in population studies to evaluate the prevalence of Ehrlichia exposure in specific regions.

NOTE: IgG Antibodies are not useful for diagnosing acute infection. IgM testing or PCR (detecting bacterial DNA) is preferred in suspected acute cases.

Testing Procedure and Interpretation

The following section outlines testing procedures and results interpretation for Ehrlichia IgG:

Test Procedure and Preparation Requirements

Ehrlichia IgG testing requires a blood sample, typically collected via venipuncture. The patient generally does not have specific preparation requirements, although it’s always important to confirm this with the ordering provider.

Normal Reference Ranges

Normal reference ranges for Ehrlichia IgG may vary slightly depending on the laboratory performing the test. However, a negative result generally indicates no detectable immune response to Ehrlichia spp. at the time of testing.

Positive results, especially in the context of clinical symptoms, suggest past or ongoing infection.

Interpreting Ehrlichia IgG Antibody Results

High IgG levels indicate past exposure but do not confirm active infection. Long-lived IgG antibodies persist even after the infection clears. If current infection is suspected, IgM or PCR testing is needed.

Low or undetectable IgG levels may suggest no prior exposure or early testing before IgG antibodies have developed. A negative IgG test does not rule out recent infection—IgM antibodies are the more relevant marker in early disease.

Animalu, C.N., MD, MPH, FIDSA. (2024, October 29). Ehrlichiosis: Background, Etiology, Epidemiology. Medscape.com; Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/235839

CDC. (2024, June 4). Tickborne Diseases of the United States. Ticks. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/hcp/data-research/tickborne-disease-reference-guide/index.html

McQuiston, J. et al. (2003, December 15). Zoonosis Update: Ehrlichiosis and related infections JAVMA, Vol 223, No. 12. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/43566197/Zoonosis_update_-_Ehrlichiosis_and_relat20160309-26225-1k286r5-libre.pdf?1457575493=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DEhrlichiosis_and_related_infections.pdf&Expires=1741997083&Signature=HqiyXW81cvLu5wIKxwNhGLqCLhE2H2lRHmXC5HBG1RMmezhAJ5yHTK96bJKxAtxkrRFkSQt-ptm5lGXurFOFlFTFf3bQQxrs-nce6TAJnE6u8GWUCRJ~zoxQMu~ZTnzY9qJbHbSPwxk9jNDjkWf3Wu0B0Oc0iiKasaJqo9nIP7MIfVmUZOeoF7RGNUzByqdod11u34RYns6w67fq5cuh~3zT2LmgjWX2RwcjBkeqLxTPQXJ0DpXTsyJerJexGp5bvs3c8QkZE7Jz4xa38KVTN10T5dLzZFpkLY5~P5qe~-7qd5nQdXK~IGS9qXwibhQyHMxf-~2V0P5zP86K39XvSA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

Parola, P., Cornet, J.-P., Sanogo, Y. O., Miller, R. J., Huynh Van Thien, Gonzalez, J.-P., Didier Raoult, Telford, S. R., & Chansuda Wongsrichanalai. (2003). Detection of Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., and Other Eubacteria in Ticks from the Thai-Myanmar Border and Vietnam. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 41(4), 1600–1608. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.41.4.1600-1608.2003

Snowden J, Simonsen KA. Ehrlichiosis. [Updated 2024 Oct 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441966/

Test for

Ehrlichia IgG